artikel | 13 juli 2025

Hypocrates under fire

A12 Utrecht – The Hague, July 11, 2025

When a screenwriter submits the story of Bosnian doctor Ilijaz Pilav and his Dutch friend and colleague Ger Kremer as a script to a film producer, it will likely be dismissed as unrealistic. However, the following scenes are not loosely based on the truth but actually happened.

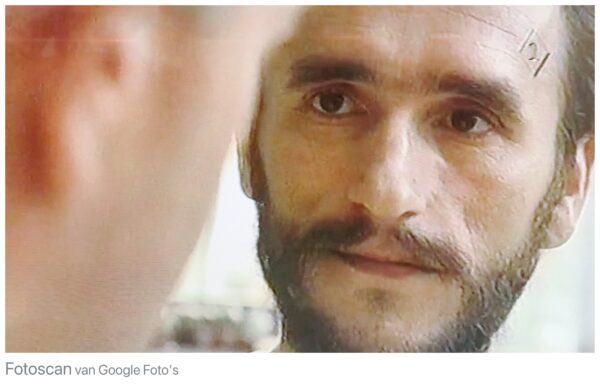

Dutchbat surgeon Ger Kremer and Ilijaz Pilav, then a trainee doctor in the operating room. Srebrenica 1995.

Scenes from the lives of two doctors in whom the war of 1995 still rages. Anyone who learns about what they went through will understand why. July 11 marks the fall of Srebrenica, genocide in post-war Europe. An event that has forever marked the lives of thousands of people, including the man next to me at the wheel. (1)

Odijk, early August 1995

The camera of Brandpunt films Ger Kremer, Dutchbat surgeon. At home on the couch, he watches NOVA. Two weeks earlier, while Srebrenica was overrun by Ratko Mladic’s troops, he was also filmed, by a Serbian cameraman. The footage is shown on NOVA that evening.

“What is happening here?” the Serb asks.

“You know exactly what’s happening here,” the colonel-doctor replies, annoyed, as he squints against the bright sun.

The enclave fell two days earlier. Four hundred lightly armed Dutch UN soldiers could not stop the Serbian advance. The promised NATO air support did not materialize. Thousands of refugees are on and around the Dutch base. As Kremer turns to the questioner, the Serbs have been transporting able-bodied men for hours. Women, children, and the elderly are being transported to safety by bus. It is scorching hot. Together with a handful of colleagues and commandos, Kremer has been busy since early morning caring for the wounded. They distribute water and guide the elderly to the buses to prevent beatings and kicks by the aggressive, heavily armed Serbian soldiers. There is chaos. The fate of the refugees is still unclear, but recent history in Bosnia casts a dark shadow. And just out of sight but not far from the compound, Kremer and his colleagues hear gunshots. From the mountains further away, the echo of artillery fire, heavier weapons, can occasionally be heard.

Gerry Kremer in Srebrenica, July 13, 1995, still serbian film footage.

Kremer is furious because he is convinced that the Serbian cameraman opposite him knows exactly what is going on. Moreover, he does not want to play a role in the aggressor’s propaganda. “You know exactly what’s happening here,” but the man filming him contradicts him: “I know nothing, I just got here.” (2)

At home in Odijk, Kremer is the first Dutchbatter in 1995 who, in front of our camera, openly testifies about the events in the enclave a few weeks earlier. His statements about the dead along the roadside, seen by a Dutchbat soldier when he left the area are repeated in the NOS News after our broadcast (Brandpunt). During our conversation, the army doctor openly distances himself from Major Franken. The Dutchbat commander, the second-in-command of the Dutchbat battalion, signed a document prepared by the Serbs on July 17 stating that the evacuation of the refugees “proceeded correctly.” “At that moment, we were sure that people had been killed in violation of the Geneva rules. So you can’t sign such a document, that’s clear,” says Kremer.

The doctor also recounts the wounded on the Dutch compound, the heat, the stench, the fear among the refugees, and the deportations. One scene has haunted him ever since; the young father handing over his baby because he is being taken away by the Serbs. He places the child in the hands of Kremer and Christina Schmitz, a German nurse from Doctors Without Borders. The man begs them to bring the child to safety. Schmitz puts a bracelet with the family name on the baby so that the father can find her if he survives.

We decide to travel to Bosnia to find out what happened. Kremer calls Christina, his former colleague. She doesn’t know what happened to the baby but remembers her name: “Irma, Irma Hasanovic.” (3)

Tuzla, August 1995

A few weeks after the fall of Srebrenica. As a film crew, we follow Ger Kremer through the lobby of the Tuzla hotel. He carries a box of shoes, brought for his friend Ilijaz Pilav, who has heard through the grapevine that Kremer is in town and is waiting for him in the restaurant. When they first met in February 1995, the Bosnian trainee doctor guided the Dutch colonel-surgeon through Srebrenica. There are holes in the soles of the Bosnian’s shoes. He gets wet feet. “When we get out of here alive, I’ll get you a new pair of shoes,” Kremer promises. Today he makes good on that promise.

Their embrace is heartfelt. The men observe each other with a loving smile. Kremer sees how emaciated Pilav is and asks him the question to which he already knows the answer:

- How are you?

“Not so good.”

Gerry Kremer and Ilijaz Pilav in Tuzla, Bosnia-Herzegovina, August 1995. Source: still film footage Ruud Denslagen.

Together with thousands of fellow sufferers, Pilav fled on foot through the mountains to here after the Serbs entered Srebrenica. But the miles-long column did not go unnoticed for long.

- Can you tell me something about the journey here?

“Inconceivable. A nightmare.”

- How many of you were there?

“About 15,000 people left with me.”

- 15,000 people?

“Who tried.”

- And how many of them arrived here?

“On the first day when I arrived here… no more than 5,000 or 6,000.”

- And the others?

“The others… are missing.”(4)

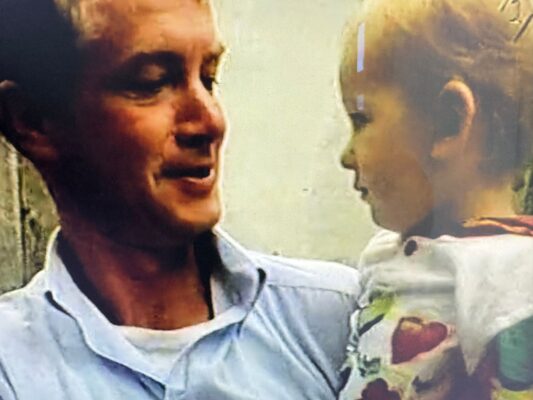

After a week of searching in refugee camps with displaced people around Tuzla, we find Irma in Srebrenik, a village just outside the city, reunited with her mother. The army doctor holds the girl in his arms, moved. The bad news is that every trace of father Nusret is missing.

Ger Kremer with Irma Hasanovic. Reunion in Srebrenik, just outside Tuzla. Source: still film footage Ruud Denslagen.

Tuzla, July 2005

It is ten years after the fall. Ilijaz Pilav organizes the first memorial march. He has invited Kremer and me to join. It is an honor. Between three and four hundred people gather. Almost all men, survivors from 1995. In their company, we walk back into history. Literally. From Tuzla, where the Death March ended at the time, to Srebrenica, where the hellish journey began. On this route, most of the deaths occurred in July 1995.

A mass grave between Tuzla and Srebrenica. Photo: Bart Nijpels.

Newly discovered mass graves testify to the genocide. Forensic investigation into the cause of death and the identification of victims has been deliberately hindered by the perpetrators. To mask their massacres, they pulverized, mixed, and spread the human remains with bulldozers over widely scattered locations.

“For me, it is a visit to the graves of my friends and family,” says organizer Pilav. We record how the victims met their end from conversations with survivors. Testimonies drenched in unadulterated horror. “A confrontation with evil,” survivor Pilav calls it. (5)

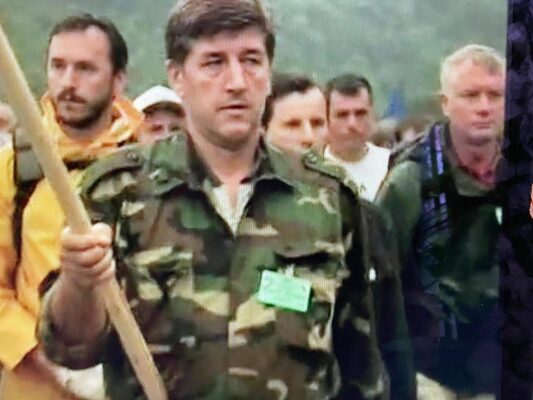

Pilav (left), Begic (middle), and Kremer (right) during the Death March. Source: still film footage Ton Vanderplas.

We pass Serbian villages. Every hundred meters, a soldier marks the route. A helicopter circles above us. At the front of the procession walks a proud man with the Bosnian flag. Teacher Ilijaz Begic wears a uniform. “I am under arms and will not demobilize until we safely arrive in Srebrenica,” he explains when asked. In the mountains, Suhad Baltic takes over the position at the head of the column. He guides us safely through the minefields that have not been cleared even after ten years. In 1995 Baltic was seriously injured during the Serbian attack.

Suhad Baltic, guide and survivor. Source: still film footage Ton Vanderplas.

At the end of the second day, I ask him how it is for him to walk this journey now. “Heavy,” he confirms bluntly. But he doesn’t want to talk about himself. He wants to talk about Dr. Kremer, who walked behind him uphill this afternoon. The surgeon who operated on him in 1995 and removed a series of shrapnel from his body. “He is the most humane person in the world. You won’t find such a man anywhere. He is praised by everyone in the Drina Valley, Srebrenica consists of four municipalities. Everyone praises him there. In ten years, everyone will still know him. Along the way, people nudge each other. Is that him? Everyone appreciates him. He saved many of us in Srebrenica. He and Ilijaz Pilav.”

The Hague, July 11, 2025

Between eight and ten thousand people murdered. Thirty years ago. It is commemorated today, as every year. In the heart of the residence, hundreds of people have gathered. At times, I feel like I’m at a standing reception. Many attendees know and greet the former army doctor. Among them are many Bosnians, or Bosniaks as they prefer to call themselves. They know Kremer, who was honored on behalf of their homeland three years ago at this same place.

From left to right: Ger Kremer, Ilijaz Pilav, and Alma Mustafic. Photo: Bart Nijpels.

The Hague, March 2022

“Thank you. We will never forget what you have done for our country,” says Ilijaz Pilav, the Bosnian doctor who survived the massacre in 1995. He has come over from Sarajevo especially for the occasion. A cautious autumn sun warms the Lange Voorhout. Around a modest stage, a group of about sixty people has gathered between the stately buildings. Bosnia-Herzegovina has today been renamed the Day of Gratitude. On behalf of his country, the ambassador also thanks surgeon Kremer for his work during the war. But his bravery is also praised. When the Serbs launched the attack on the enclave and it rained mortars, Kremer received the order from his commander, Major Franken, to take shelter with the Dutch blue helmets. With helmet on and bulletproof vest on, they had to go into the bunker. But the doctor, seeing trucks with wounded arriving at the compound, refuses. Franken threatens to drag him before the Court Martial. Kremer replies: “Fine. And stick that order where the sun doesn’t shine. I’m here to help people.” The doctor remains true to Hippocrates and, accompanied by two commandos, cares for as many wounded as he can. “He chose the right side of history,” Ilijaz Pilav recalls on stage. He hands over the award and embraces his friend.

The Hague, July 11, 2025

Today, the German newspaper Die Zeit publishes a five-part podcast series and a major article. The newspaper has tracked down Irma Hasanovic, the baby handed over by her father to Kremer and Christina Schmitz, the German nurse, during the fall of Srebrenica.

Irma, now an adult woman, married and living in Slovenia, says in the publications that she does not understand why the Dutch UN soldiers did not intervene when the Serbs deported the Bosnian men, including her father. From her perspective, a understandable question. The simple answer is that the poorly armed Dutch blue helmets had nothing to counter the Serbian superiority. For Irma, of course, an unsatisfactory explanation. But even the complicated and nuanced analysis of the circumstances that led to the drama will not be able to take away her anger and grief. The cold choices of the world powers preceding what happened in Srebrenica do not diminish the pain of the survivors and relatives. On the contrary, they fuel it. (6)

Part three of the German podcast series is titled “Der Blauhelm der nicht eingriff.” (7) Just below the heading is a portrait photo of Kremer. “It is Irma’s perspective. Our title team chose this title,” say the podcast makers in response to Kremers disappointment. But the title is not printed as a quote, and thus Die Zeit presents it as a fact that Kremer is the blue helmet who did not intervene. In the announcement, the journalists emphasize it again. “When Irma was separated from her father in 1995, a Dutch soldier stood next to her: Gerry Kremer. As part of a UN mission, he was supposed to prevent the violence from escalating,” Kremer, who was no soldier but a surgeon, did not carry a pistol on his hip but a stethoscope around his neck, is portrayed as a soldier who did nothing and let the violence escalate.

The commemoration, in the middle, Gerry Kremer. Photo: Serge Janssen

During the commemoration, a young Bosnian-Dutch woman sits in front of us. She works at the Ministry of Social Affairs, hears what we are talking about, and asks a few questions. Kremer answers, partly in her mother tongue. The next day, she sends him a message via social media that largely erases his sadness about the German publication and deeply moves him. “As far as I’m concerned, it’s a downright journalistic blunder to frame you that way (…). During my search, I also came across numerous other articles about your selfless dedication in Srebrenica. For what it’s worth, I want to thank you for that. I am incredibly impressed – also by your Bosnian vocabulary.”

Sources:

- https://www.stinglikeabee.nl/de-oorlog-in-een-arts/

- https://vimeo.com/162902666

- https://www.stinglikeabee.nl/op-zoek-naar-irma-i/

- https://www.stinglikeabee.nl/op-zoek-naar-irma-deel-ii-brandpunt-240995/

- https://www.stinglikeabee.nl/de-mars-van-de-dood/

- https://www.stinglikeabee.nl/waarom-srebrenica-moest-vallen/ (version in english: https://www.vpro.nl/speel~WO_VPRO_1254460~why-srebrenica-had-to-fall-2doc~.html

- https://www.zeit.de/serie/irma